Portraits of Those Who Were Salvaged

Gwangsun Park

For a long time, Gwang Sun Park has been painting oil portraits on discarded plywood that he finds on the streets or at construction sites. This unusual process is emblematic of the artist’s overall style and goals. As opposed to a well-prepared canvas, a piece of used plywood instantly elicits thoughts of alienation, exclusion, and disposal. The mere act of painting on such an inappropriate surface, without even a layer of gesso as a base, is itself a performative gesture that implies resistance to convention and disengages the work from conceptual conditions. The resulting paintings exist as compelling evidence of the artist’s choices and gestures.

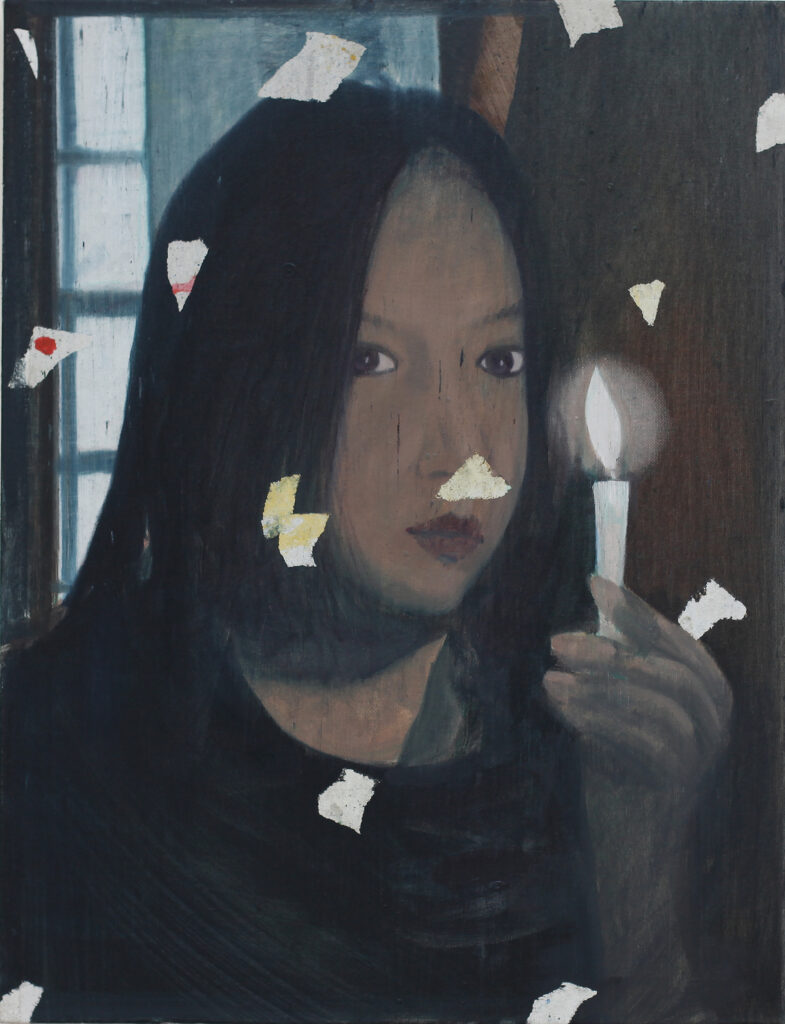

Park’s appropriation of discarded panels also helps to extend the relationship between the artist and artwork beyond the usual production process. His works remind us of the encounter with the object, while also evincing relationships forged by fate. Rather than planes for two-dimensional representations of people, the panels become three-dimensional forms of actual people, much like totems. He sometimes uses pliers or other tools to roughly cut or rip away the background behind the figures, transforming the works into some type of relief. This technique also furthers the illusion that the figures exist in real space, rather than inside a pictorial background. As such, his subjects come to inhabit an unspecified area between two and three dimensions. In Thrill (2012), Park painted a faint portrait on a thin layer of plywood, which he then attached to a white panel. It seems that the plywood had not yet attained an independent position. But in Broken Faith (2016), two figures are united within a single wooden board: a large silhouette resembling a woman wearing a shawl and holding a candle, which contains the smaller, darker figure of a man. While these two figures are intrinsically combined as one, they each have their own outlines that were cut separately.

Gwang Sun Park always paints his figures very thinly, thereby allowing the wood grain to remain visible. As the untreated wood absorbs the paint, the tone of the faces is slightly darkened. In some cases, he scrapes off or rubs the paint after it has been applied. In Three Sisters (2018), for example, he wiped the paint vertically on the plywood. Hence, white paint from the veil of the central woman drips across her face, like a ruined painting, while the facial expressions of the two other women are almost rubbed out. Through such materials and methods, Park’s works take on a sense of poverty and destitution, transcending mere expression or representation to enter the “economic” realm of painting. Similar to Thrill, Sorrow Wolf (2020) was made by attaching a piece of painted plywood to a canvas. But here, the background canvas was intentionally stained with paint and dust, like a old floor covering that has been endlessly trod upon for a long time.

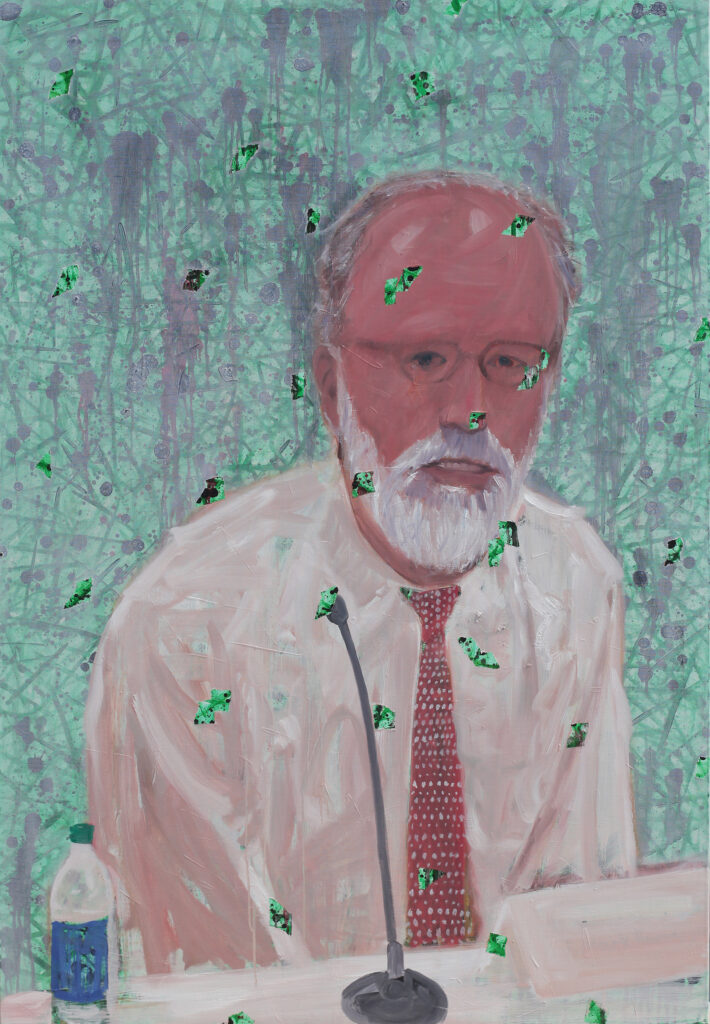

Since 2019, Gwang Sun Park has increasingly used canvas in his works. Even so, he has maintained his signature method of quick and concise painting, and also continues to damage the surface in interesting ways, such as applying and tearing away pieces of masking tape, removing patches of paint. They Don’t Remember Me as Much as I Thought (2020) is a portrait of someone looking straight ahead, but the face is very roughly rendered with a blurry gaze and expression. Moreover, pieces of the face have been removed with tape, reminding us that it will disappear someday. This sensation is extended in Too Chairs (2021) and Ramseyer Poisoned the Well (2021), in which the tape was used to damage the entire plane of the painting, not just the figure. More than mere representations, Gwang Sun Park’s paintings suggest negative memories or emotions. Recalling the “spells” of Antonin Artaud (ethereal drawings combining images and text), Park’s works are like intermediaries derived from real-life relationships or experiences.

Artist’s Note

Space is established and progresses in time. The coal mining industry, which flourished until the 1980s, began to decline in the 1990s. With the decline, coal mining regions such as Jeongseon, Taebaek, and Samcheok became more and more ruined as time passed. Those living in the midst of this decline have lost their way due to economic difficulties. In the famous poem “Natasha, the White Donkey, and Me,” Baek Seok wrote, “You renounce the world because it’s in disarray, but going to a remote mountain doesn’t mean you’re free from the world.” Like the poem, all of the people in the blind end of a mine gallery have their own stories and hopes for life that brought them there. So we go back to different places and times and live today, breathing in this contemporary megalopolis. The labor-intensive industries that formed the core of Korea’s industrialization gradually declined. Population decline and industrial restructuring are adjustments to imbalances in supply and demand. In the space created by historical times, we stay for a while, spending our own time and creating something new. As society has developed, each generation has been able to think a little more independently than the previous generation. In a way, after the time when people had to risk their lives in the mines, we have more time to polish the rough stones. Through my works, I want to create a lasting time in our memories and our culture. To create such a sustainable story, focusing on the individuals, I snoop around today’s society as well.